Indexing

In this post, I’m gonna introduce some basic algorithm of web doc indexing.

Blocked sort-based indexing

BSBIndexConstruction()

n = 0

while ( all documents have not been processed )

do n = n+1

block = ParseNextBlock()

BSBI-Invert(block)

WriteBlockToDisk(block, fn)

MergeBlocks(f1,...,fn;f_merged)

There are 4 steps : (i) segements the collection into parts of equal size, (ii) sorts the termID-docID pairs of each part in memory, (iii) stores intermediate sorted resultes on disk, and (iv) merges all intermediate results into final index.

The algorithm parses documents into termID-docID pairs and accumulates the pairs in memory until a block of a fixed size is full (ParseNextBlock). We choose the block size to fit comfortably into memory to permit a fast in-memory sort. The block is then inverted and written to disk.

Inversion (BSBI-Invert) involves two steps. First, we sort the termID-docID pairs. Next, we collect all termID-docID pairs with the same termID into a postings list, where a posting is simply a docID. The result, and inverted index for the block we have just read, is then written to disk.(WriteBlockToDisk)

In the final step, the algorithm simultaneously merges the ten blocks into one large merged index.(MergeBlocks)

Single-pass in memory indexing

SPIMI-INVERT(token_stream)

output_file = NEWFILE()

dictionary = NEWHASH()

while(free memory available)

do token = next(token_stream)

if term(token) does not exist in dictionary

then postings_list = AddToDictionary (dictionary, term(token))

else postings_list = GetPostingsList(dictionary, term(token))

if full(postings_list)

then postings_list = DoublePostingsList(dictionary, term(token))

AddToPostingsList(postings_list,docID(token))

sorted_terms = SortTerms(dictionary)

WriteBlockToDisk(sorted_terms,dictionary,output_file)

return output_file

//need to merge blocks out of this function

Blocked sort-based indexing has excellent scaling properties, but it needs a data structure for mapping terms to termIDs. For very large collections, this data structure does not fit into memory. A more scalable alternative is single-pass-in-memory indexing or SPIMI. SPIMI uses terms instead of termIDs, writes each block’s dictionary to disk, and then starts a new dictionary for the next block. SPIMI can index collections of any size as long as there is enough disk space available.

SPIMI-INVERT is called repeately on the token stream until the entire collection has been processed. Tokens are processed one by one during each successive call of SPIMI-INVERT. When a term occurs for the first time, it is added to the dictinary (best implemented as a hash), and a new postings list is created.

A differece between BSBI and SPIMI is that SPIMI adds a posting directly to its postings list. Instead of first collecting all termID-docID pairs and then sorting them, each postings list is dynamic and it is immediately available to collect postings. This has two advantages: It is faster because there is no sorting required, and it saves memory because we keep track of the term a postings list belongs to , so the termIDs of postings need not be stored. As a result, the blocks that individual calls of SPIMI-INVERT can process are much larger and the index construction process as a whole is more efficient.

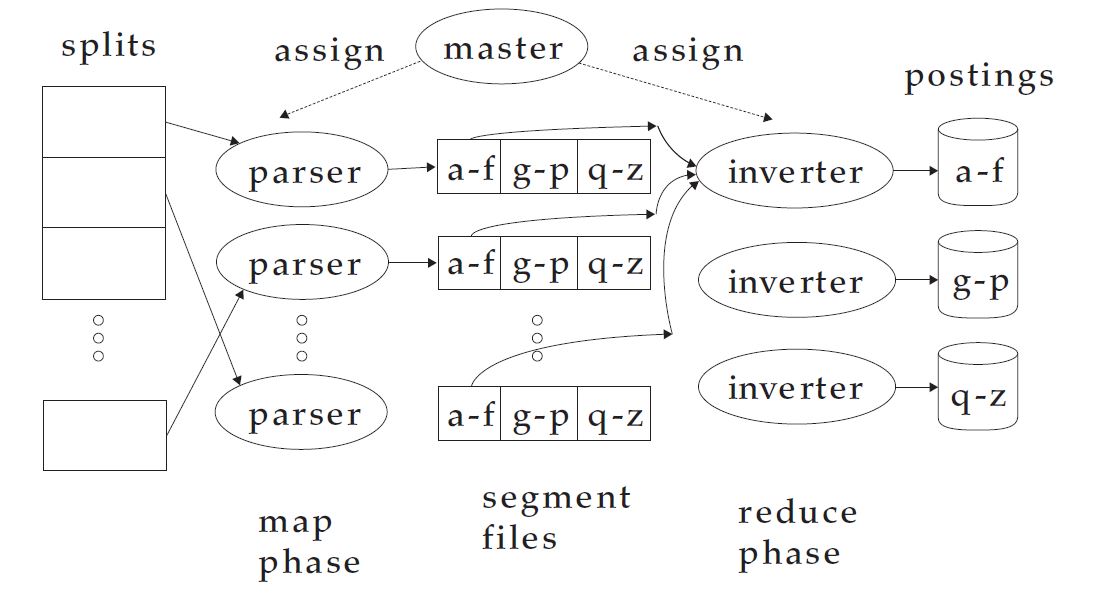

Distributed indexing

Collections are often so large that we cannot perform index construction efficiently on a single machine. This is particularly true of the WWW for which we need large computer clusters to construct any reasonably sized web index. Web serach engines, therefore, use distributed indexing algorithms for index construction. The result of construction process is a distributed index that is partitioned across several machines either according to term or according to document.

In general, MapReduce breaks a large computing problem into smaller parts by recasting it in terms of manipulation of key-value pairs. For indexing, a key-value pair has the form (termID, docID). In distributed indexing, the mapping from terms to termIDs is also distributed and therefore more complex than in single-machine indexing. A simple solution is to maintain a (perhaps precomputed) mapping for frequent terms that is copied to all nodes and to use terms directly for infrequent terms. We assume that all nodes share a consistent term to termID mapping.

The map phase of MapReduce consists of mapping splits of the input data to key-value pairs. This is the same parsing task we also encountered in BSBI and SPIMI, and we therefore call the machines that execute the map phase parsers. Each parser writes its output to local intermediate files, the sgement files.

For the reduce phase, we want all values for a given key to be stored close together, so that they can be read and processed quickly. This is achieved by partitioning the keys into j term partitions and having the parsers write key-value pairs for each term paritition into a separate segment file. Collecting all values(docIDs) for a given key (termID) into one list is the task of the inverters in the reduece phase. The master assigns each term partition to a different inverter - and, as in the case of parsers, resigns term partitions in case of failing, or slow inverters. Each term partition is processed by one inverter.

Dynamic indexing

So far, we have assumed that the document colleciton is static. This is fine for collections that change infrequently or never. But most collections are modified frequently with documents being added, deleted, and updated. This means that new terms need to be added to the dictinary, and postings lists need to be updated for existing terms.

The simplest way to achieve this is to periodically reconstruct the index from scratch. This is a good solution if the number of changes over time is small and a delay in making new documents searchable is acceptable.

If there is a requirement that new documents be included quickly, one solution is to maintain two indexes: a large main index and a small auxiliary index that stores new documents. THe auxiliary index is kept in memeory. Seaches are run across both indexes and results merged. Deletions are stored in an invalidation bit vector. We can then filter out deleted documents before returning the search result. Documents are updated by deleting and reinserting.

LogarithmicMerge()

Z0 = empty

indexes = empty

while true

do LMergeAddToken(indexes, Z0, GetNextToken())

LMergeAddToken(indexes, Z0, token)

Z0 = Merge (Z0, {token})

if Z0's size = n

then for i = 0 to inf

do if I_i is in indexes

then Z_i+1 = Merge(I_i,Z_i)

//Z_i+1 is a temporary index on disk

indexes = indexes - {I_i}

else I_i = Z_i

// Z_i becomes the permanent index I_i

indexes = indexes + {I_i}

break

Z0 = empty

n is the size of the auxiliary index and T is the total number of postings. We can achieve O(T log(T/n)) for time complexity by introducing Indexes I_0, I_1, … of size . Each posting is processed only once on each of the log(T/n) levels.We trade indexing efficiency gain for a slow down of query processing; we need to merge results from log(T/n) indexes as opposed to just 2(the main and auxiliary indexes)

Having multiple indexes complicates the maintenance of collection-wide statistics. In fact, all aspects of an IR system: index maintenance, query processing, distribution, and so on are more complex in logarithmic merging. Because of this complexity of dynamic indexing, some large search engines adopt a reconstruction-from-scratch strategy. They do not construct indexes dynamically. Instead, a new index is built from scratch periodically. Query processing is then switched from the new index and the old index is deleted.

Reference:

“An Introduction to Information Retrieval”

MapReduce , Dean and Ghemawat(2004)